For instructions how to uninstall Little Snitch 4, see here.

How to Find and Stop the Workplace Snitch. Updated: May 13, 2016. One of the first lessons that most people learn in grade school is, 'Nobody likes a tattletale.' But some people never get this idea through their heads, and, eventually, these pint-sized snitches grow up and join the workforce, where they make colleagues' and managers' lives. On my MacBook Pro, I set Little Snitch to ask for nsurlsessiond connection attempts. Here you see it attempting to connect to valid.apple.com right after I plug my MacBook Pro into the power adapter (more on that later). The CPU usage of trustd is 0% at that point.

In order to uninstall Little Snitch 5, just move the Little Snitch application from your Applications folder to the trash in Finder.

This will completely remove all components associated with Little Snitch, including all its system extensions and helper tools.

IMPORTANT: Do not remove the Little Snitch app by any other means (like Terminal or some third party app-removal tool) because otherwise macOS won’t remove the Little Snitch system extension!

Configuration files

Your configuration data will not be deleted. So if you decide to reinstall Little Snitch at a later point, your rules and preferences will still be in place.

The configuration files are stored at the following locations

The ~ (tilde character) refers to your home folder.

How to check if Little Snitch was successfully uninstalled

If you wish, you can then run the following two commands in a Terminal window to check if the uninstallation was successful:

Show all currently installed system extensions of Little Snitchsystemextensionsctl list | grep activated | grep at.obdev.littlesnitch

Show all currently running components of Little Snitchps -ax | egrep 'Little Snitch|littlesnitch' | grep -v grep

When Little Snitch is uninstalled, both commands should yield an empty result.

Troubleshooting

Due to a bug in macOS, the uninstallation may fail in some rare cases, causing the Little Snitch system extensions to remain installed after moving the app to the trash. To recover from this situation, please do the following:

- Reinstall the current version of Little Snitch 5 in your Applications folder (either by putting it back from the Trash or by downloading it from our website).

- Start the App with the Option key held down.

- You will be presented with a window showing the current installation status of all Little Snitch components.

- Click the lock icon at the bottom left corner of the window to authenticate as an administrator.

- Click on “Network Extension” and choose “Uninstall”.

- If the “Endpoint Security” system extension is shown as installed, uninstall it as well.

- Quit the app and move it to the Trash in Finder.

At a glance

Cons

Our Verdict

Our Macs can be chatty even when we wish they weren’t. Apps, and even the OS itself, regularly reach out to the rest of your local network and to the Internet to probe, query, and blab. Little Snitch 3 intercepts these requests and presents them to you for inspection and approval. The latest update to the software adds inbound-connection management, too. Little Snitch has graduated from being a sort of outbound-only firewall with notifications to being a full-fledged firewall product with a friendly interface that informs you about any network-related activities.

Can't Quit Little Snitch

OS X’s built-in firewall, when enabled, functions based on services and applications, allowing only inbound connections aimed at particular pieces of software—for example, a connection to iPhoto’s shared-library service. But the OS X firewall can’t be configured to allow a connection from a particular Internet protocol (IP) address. Little Snitch offers this type of functionality, but it reveals this power in stages, allowing a simple approach for those who want security without fuss, while using configurable rules to provide levels of deeper and deeper access for those who want more-precise control.

As in previous versions, Little Snitch’s most obvious use is in alerting you to the network activity of applications and low-level software. For instance, launch Google Chrome, and Little Snitch warns you that the browser is attempting to connect to www.google.com (to check for updates, ostensibly). Should Little Snitch let it proceed, and, if so, for how long and with what limits? The utility even differentiates between IP addresses and ports. (An IP address is a destination, like an apartment building; a port is like a specific apartment within the building.)

Little Snitch comes configured to allow common activities—for example, Safari requesting data from port 80 (standard Web pages) and port 443 (https-secured pages)—to pass through without notice. Many OS X system daemons, autonomous bits of low-level software, also get preapproved. But even these passes are explicitly allowed via rules that you can view, with descriptions, in the Little Snitch Configuration app.

For previously unknown connections, Little Snitch presents a dialog box that shows you the requesting app’s icon, its name, and what it’s attempting to do. Using the previous example, you might see an alert that Google Chrome is trying to connect, using port 80, to www.google.com. Click Details to get even-more-detailed information. Clicking Allow or Deny adds a rule to Little Snitch’s configuration, bypassing this dialog in the future for varying degrees of specificity and periods of time.

For any particular connection, the program lets you choose how specific your Allow or Deny rule should be: Any Connection for all outbound traffic, a port number for all outbound traffic over that port, a domain name (or IP address) for any traffic to that domain, or, the most specific, a domain name (or IP address) paired with a port.

You also control how long your rule remains in effect. Obviously, the Forever button makes it a permanent rule (which can be deleted or modified using the configuration program). But the duration pop-up menu to the right, which has expanded its range of choices since Little Snitch 2, lets you set the rule to expire after the affected program quits, after you log out, when the Mac is restarted, or for a specific length of time.

Assuming the affected app is one you use frequently and you want to allow to do its thing, you’ll likely choose Allow and Forever—most programs engage in benign activity to specific domains. But when you see an alert that doesn’t pass the smell test, that’s when you’ll want to limit the connection (for a period of time or Until Quit are usually good choices) or deny it altogether.

For example, some programs make it their business to send back information about your usage, and you just don’t want them to do so. Others sniff or broadcast over the local network to determine if multiple copies of an app are running or for more-nefarious information-gathering purposes. I say, “Deny!” In some environments—government, military, or legal, medical, or financial businesses—there may be other security concerns that dictate whether or not you should allow such connections.

As you approve and deny connections, thus creating the appropriate rules, you train the software over time, receiving warnings about communications you want to keep an eye on—or for software that has no business calling outbound. If you use many apps every day, the initial setup period can feel laborious as you teach Little Snitch how to handle each app. Things soon settle down.

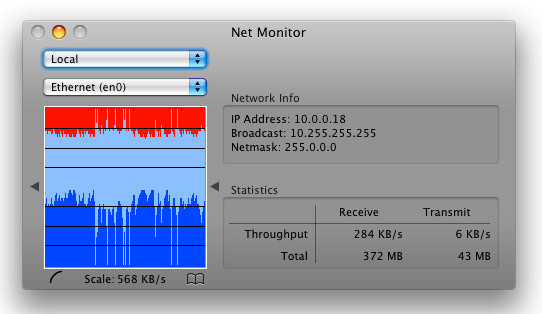

Quit Little Snitch

For keeping track of what apps are currently being monitored by Little Snitch and what they’re doing, Little Snitch’s already useful Network Monitor window has become more sophisticated in version 3. The window shows every recently active program, a gauge of recent bandwidth consumption, and all the host/domain combinations to which each program has connected. Click any app to view a historical bandwidth-usage graph; you can adjust the time period shown. Right-click (or Control-click) an app’s main entry or any server, and you can create a new rule based on that selection. Double-click a graph, and Little Snitch offers exceedingly detailed connection information, including total traffic and the most-recent time data was sent.

Previous releases of Little Snitch could block only outbound traffic, warning you only when programs and low-level software attempted to make a connection outside your computer. Little Snitch 3 allows control of incoming connections, too. Internet criminals and vandals are constantly probing for open connections to servers and individual computers, such as attempting to create a terminal session via SSH (Secure Shell) using common account names and passwords. Blocking access reduces your window of exposure, and offers more peace of mind, too.

(While it’s true that the focus of most security software has largely shifted to detecting malicious programs loaded onto Web pages, blocking inbound traffic remains a way to keep your computer protected from potential new threats before they’re known and patched. Most home users are behind routers that use Network Address Translation, which effectively blocks direct connections from the Internet. Businesses, and even coffeeshops, however, are more likely to have Internet-routable addresses, and the IPv6 network-addressing rollout finally underway can expose computers to new threats by making them directly reachable, too. Little Snitch helps in all these scenarios, as it doesn’t differentiate from where traffic is coming and going. It just identifies and alerts you to new connections—or lets those connections pass if they meet existing rules.)

Little Snitch is the only security software that I recommend wholeheartedly to an entire range of users, from beginner to super sophisticated. It provides network—and privacy—protection while being easy to use and train, and it’s powerful enough for demanding users.

Want to stay up to date with the latest Gems? You can follow Mac Gems on Twitter.

Note: When you purchase something after clicking links in our articles, we may earn a small commission. Read ouraffiliate link policyfor more details.

Quit Little Snitch Book

- Related: